A large number of minority voters and candidates participated in the 2020 Election in Arkansas.

In all 50 states, the share of non-Hispanic White eligible voters declined between 2000 and 2018, according to the Pew Research Center. During that same period, Hispanic voters began to make up increasingly larger shares of the electorate in every state. The number of eligible Hispanic and Black voters in Arkansas increased by 57,000 and 56,000, respectively, during that time.

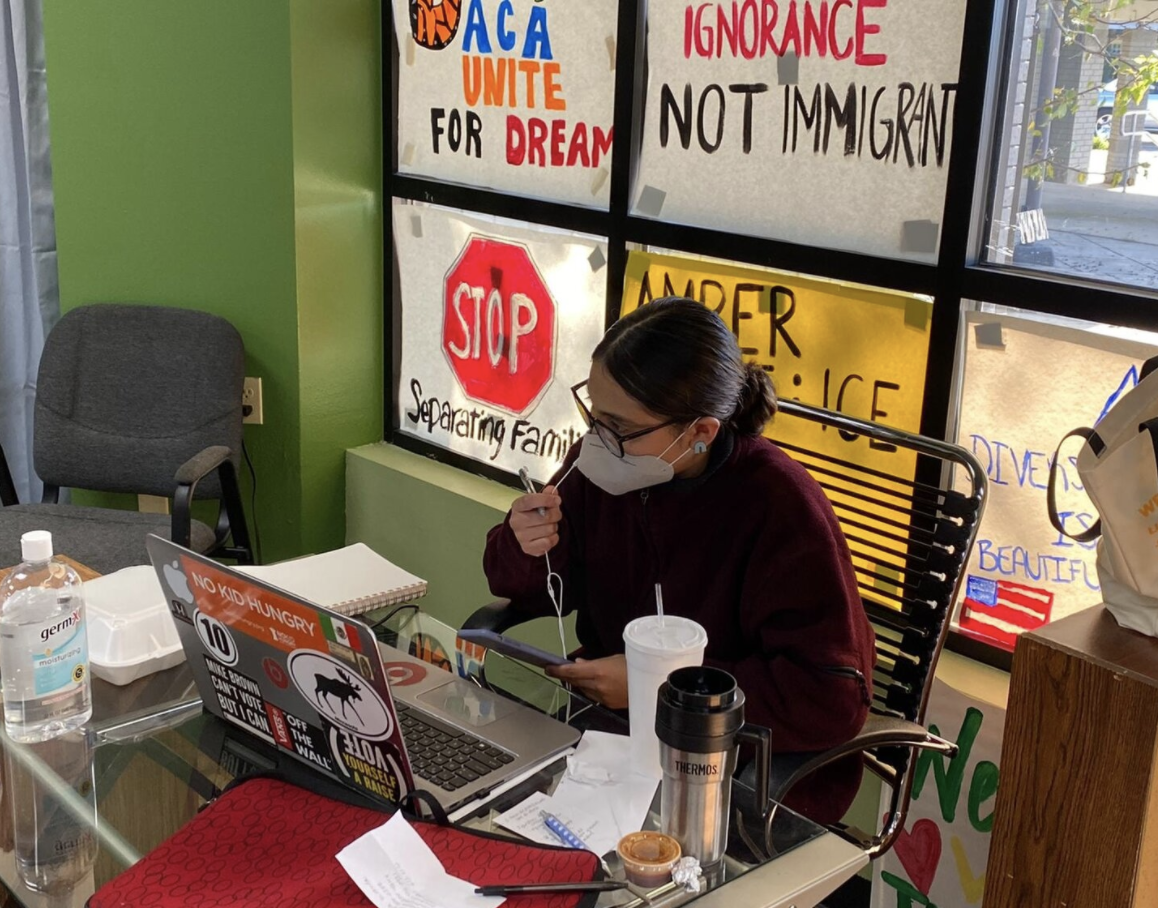

While the breakdown of voters for the 2020 Election is not yet known, Mireya Reith, executive director of Arkansas United, says based on data the immigrant advocacy group collected on the phone and what they observed while present at the polls, a large number of minority voters participated in the electoral process. Being part of national policy is one reason communities of color, including immigrants, showed up to the ballot box.

“President Trump’s anti-immigrant stances and many times racist and derogatory comments did rally many of our voters,” she says.

Another motivator was the trust that has been built by some state legislators who have developed a track record of supporting policies that benefit people of color.

Rep. Megan Godfrey, for example, is a Democrat who represents the state’s 89th District, which includes a portion of the diverse city of Springdale. During her first term in the Arkansas House, she helped pass legislation that allows the Arkansas State Board of Nursing to grant licenses to participants in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA program. She won reelection Tuesday.

“We believe [the policies] benefit all Arkansans, but they address some of the systemic barriers for our community and now with that track record, our community was inspired to send them back with even a bigger mandate to keep being champions for our life perspectives and our concerns and issues,” Reith says.

Having more people of color run for office in Arkansas is another reason minority voters showed up to the polls. This gave better confidence, especially to new voters, Reith says, that the candidates seeking office would be open to conversations about needs and issues that communities of color are confronting.

“In the past we frequently heard in our get-out-the-vote efforts that our community would rather not vote than vote for the wrong person and had expressed concern many times about not seeing surnames or names in general of folks they recognize and we think that this election was a huge step forward,” she says.

Because of the pandemic, Arkansas United conducted voter outreach efforts over the phone. The nonprofit made close to 80,000 phone calls this election cycle.

“Due to COVID-19 we had higher pressure than ever to speak to our community by phone and by text message,” Reith says. “We also sent over 150,000 bilingual text messages to our community to be able to make sure they had the information to be part of this process.”

Arkansas United also worked on the absentee ballot process, put together a voter protection effort, provided transportation and extended interpretation to the community. Reith says they saw a last-minute surge of Marshallese and Latino voters on Election Day, but there were inadequate bilingual poll workers. Language access continues to be a barrier for many new voters in Arkansas, she says.

According to Arkansas Law, no person other than the following shall assist more than six voters in marking and casting a ballot at an election: a poll worker, the county clerk during early voting or a deputy county clerk during early voting.

To challenge the law, MALDEF, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, on Monday filed a lawsuit and request for a temporary restraining order on behalf of Arkansas United and its executive director. The lawsuit names Secretary of State John Thurston and other election officials as defendants.

Griselda Vega Samuel, MALDEF Midwest Regional Counsel, says the Arkansas law is a very difficult restriction and it divests of the resources Arkansas United has.

“In no other election as this, it has been so important to get our Black and Brown communities out there and so we want to make sure that everyone who can vote, has the access to vote especially when our federal law already says that any person who needs that assistance should have that assistance,” Samuel says.

“In no other election as this, it has been so important to get our Black and Brown communities out there and so we want to make sure that everyone who can vote, has the access to vote especially when our federal law already says that any person who needs that assistance should have that assistance,” Samuel says.

Attorneys argue that restrictions in the Arkansas election code violate the 1965 Voting Rights Act guarantee that any voter who requires assistance in voting, including those with limited proficiency in English, may bring a person of their choice to assist them with casting a ballot. By limiting the number of voters a person can assist, Arkansas impedes the ability of limited English proficient voters to participate in an election, the complaint says.

This is a really valid lawsuit, Samuel says, and they are waiting to see what the court will do.