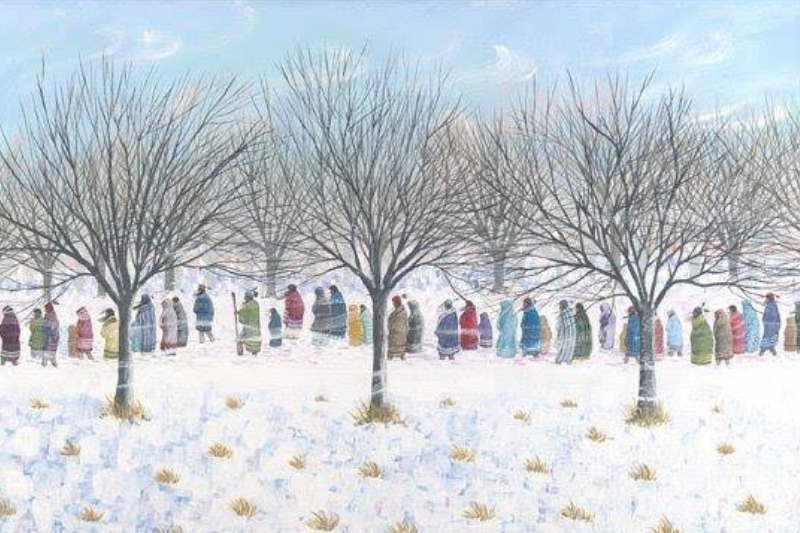

Artwork commemorates American Indians who walked the Trail of Tears

Johnnie Diacon doesn’t create a lot of Trail of Tears artwork, so his mural for the Museum of Native American History is special.

“I really don’t like to depict the suffering like that and make money off of it,” Diacon says. “But when I do do these pieces, like for this mural, it’s a commemorative piece to let people know that this is what happened and that we’re still here, and we’re in the situation we are because of this.”

The new work commemorates the forced relocation of tribes under the Indian Removal Act, which was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson in 1830. Creating a mural to depict this history is important, the Tulsa-based artist says, because it’s how his people ended up in Oklahoma. It’s part of who he is.

“To us the Trail of Tears is almost like a Holocaust,” Diacon says. “It’s a memorial when we do these pieces. It’s our ancestors, our relatives, and it’s an honor and a tribute to them.”

The Bentonville museum commissioned the work as part a joint exhibition with Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. The mural will be comprised of three large panels, each measuring about four by eight feet. Once completed, the artwork will depict a line of Native Americans traveling along the Trail of Tears and it will be installed on the museum’s exterior southern wall.

Diacon, an enrolled citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma, has been MONAH’s Native American Artist of the Month during November and director Charlotte Buchanan-Yale says it’s an honor to feature his work. For the joint exhibition, Buchanan-Yale says she really wanted to feature a local artist.

“Sometimes we forget our own local artists and I can’t think of a better person than Johnnie to bring in during this time and spotlight his talent,” she says.

Johnnie Diacon traces his roots as an artist back to his late father who was a sign painter. His father moved their family to Northwest Arkansas for work and Diacon helped with the business when he was older. A few years after graduating high school, Diacon enrolled in Bacone College in Muskogee, Okla.

“They had an Indian Art program there so I enrolled there and that began my career in art,” he says. “Then I went to the Institute of American Indian Arts out in Santa Fe and so I’ve been entering shows for the last 40 years and doing paintings.”

One teacher described Diacon’s style as schizophrenic because he changes his approach and can go from a flat style to a more contemporary look.

“It just depends what I’m in the mood to do or what I’m depicting, how I want to depict that scene,” he says.

Diacon was first exposed to flat style Indian art while visiting a doctor to help with his poor eyesight.

“This doctor was a collector of the old flat style Indian art and that was my first experience where I could actually see because I was legally blind without glasses,” Diacon says. “I saw the artwork for the first time, I saw these images and it stuck in my head. And this is as a young boy and so I was trying to replicate those images that I saw using my dad’s sign paints.”

Johnnie Diacon draws inspiration for his art from his culture, but his work is not always historical. His pieces may depict scenes of everyday life, like people cooking for example, but the people in it are usually Native Americans. Sometimes people don’t recognize Diacon’s work as Indian Art because it’s different from what they expect.

“They want to see Plains Indians with the headdresses and on horses and buffalo hunts and things like that, which is not what my people did,” he says. “So a lot of times when I produce work on my people, the Muscogee, we’re southeastern Indian. We’ve got different customs, different traditions, different attire when we perform ceremonies.”

While people within his tribe recognize and connect with the subject matter of his artwork, others may not.

“That’s one of the dilemmas I run into with non-natives when I get into art markets — they may pass it over because they like it, but they can’t relate to it because it’s not what they think an Indian piece of work should look like,” he says.

Highlighting the diversity of Native American culture is one of the goals of the Museum of Native American History, director Charlotte Buchanan-Yale says.

“That’s one of our main missions is to debunk that everybody is a Plains Indian and to highlight that diversity of our collection, as well as the people that we work with,” she says.

Johnnie Diacon is just starting to work on the yet-to-be named mural, but he expects to finish the project in January 2021.

The Museum of Native American History is closed to the public because of the pandemic, but it does offer virtual programming. More information is available at www.monah.us