REPRINTED FROM “THE PRESERVATION” | VISIONAIRI

Black Geographies & White Terrorism

The shooting massacre on May 14, 2022, brought unfathomable devastation to families and communities throughout Buffalo and the nation.

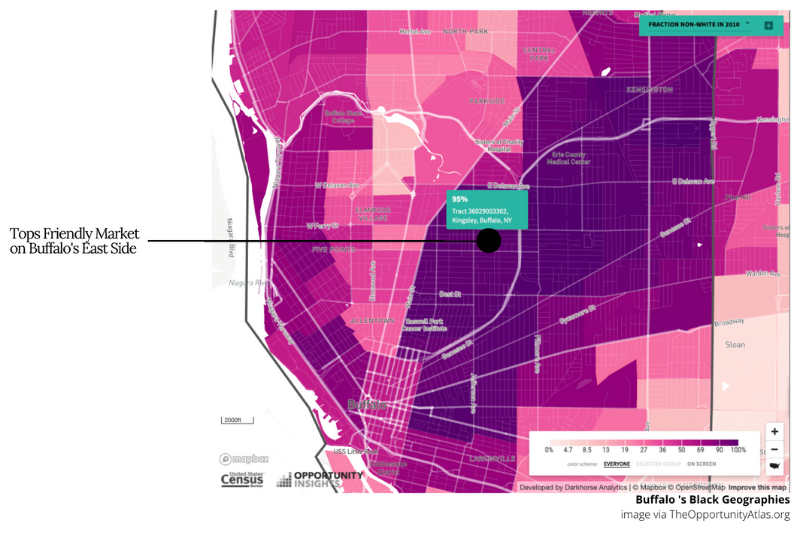

Ruthless and deliberately, a white gunman opened fire at the Tops Friendly Market on Jefferson Avenue. Ten lives were taken, and three other individuals were wounded. As America faces the aftermath of another racist domestic terrorist, it is clear we wrestle with the residue of history and progress.

Racially motivated violence is long part of our national heritage, and the selection of that specific store, in that specific neighborhood was intentional and demonstrated the outcomes of modern urban planning.

The gunman understood where to inflict the most harm to Black people in Buffalo, in many ways due to the legacy of Black geographies in the nation’s urban spaces.

Domestic terrorists use the social awareness of urban Black geographies as a tool to callously uphold white supremacy in America.

In Buffalo, Black populations increased by 4,500 in 1920 and within a decade there were 13,500 coming annually and relocating in Buffalo’s East Side. Black Buffalo residents created self-reliant communities and established their own thriving economies.

Featuring a rich heritage of Black life and culture, Buffalo’s location next to the Canadian border made the city a hub for Black migration well before the onset of emancipation following the Civil War. Buffalo featured the tenth largest concentration of Black residents in the North by 1855.

Enslaved African Americans traveled to Buffalo as one of the final American stops on the underground railroad, often sheltering in caverns and tunnels under local businesses such as the Eagle Hotel. Economic opportunities and escape from the southern racial caste provided ample incentives for African Americans to migrate to the city throughout the twentieth century.

20th Century public policies reshaped Black life in urban Buffalo

Urban renewal policies during the mid-century responded to this increasing Black presence in cities around the nation. Buffalo was no different. These policies reshaped urban landscapes and relocated numerous Black communities in the cause of progress.

Progressive era values intertwined with the spirit of Jim Crow, undergirded the planning philosophies for America’s urban renewal projects. Greater Black presence in urban spaces like Buffalo, prompted white urbanites flight to burgeoning suburban communities.

Anxieties over the growing understanding that segregation was systematically being dismantled in education throughout the 1940s and 1950s emboldened the coalitions of city officials, local civic leaders, and economic interest to harness urban redevelopment for their goals to maintain social segregation and dominance.

Domestic terrorists use the social awareness of urban Black geographies as a tool to callously uphold white supremacy in America.

In the age of the Cold War, the Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways was developed as a tool for national defense and to make room for America’s growing fondness for the automobile. While interstate construction was promoted as business friendly urban development, the reality that their construction routes often targeted Black neighborhoods is well understood.

These realities were not hidden but packaged in modern, ornately modeled and documented publications and reports rolled out to Buffalo’s public in 1953. Interstate construction impact reports and survey analysis projects utilized modern technology and expertise – another progressive hallmark – to present clean and nonthreatening designs, downplaying their devastating impact.

Using progressive language such as eminent domain, traditional Black communities’ lands were devalued and often selected as the path of least resistance for interstate highway developers.

Cold war era containment ideology was employed domestically through the growth of interstate systems in cities around the country including Buffalo. African Americans were confined into increasingly barren predetermined inner-city spaces through interstate construction, often out of visible site of suburban interstate commuters.

The Scajaquada Creek Expressway and the Kensington Expressway, the first and second links in Buffalo’s interstate system demolished neighborhoods and park spaces. This process in Buffalo was consistent in time and execution with urban renewal and interstate highway system construction projects around the country.

The Kensington expressway opened in 1967 amid social and economic conflict, driving through the city’s only middle-class Black neighborhood. Fifty years later, the Tops Friendly Market remained one of few grocery options for Buffalo’s East Side, evidence of the alienation and decimation created by urban renewal and interstate construction.

Black Geographies and White Terrorism

The gunman’s decision to target Tops Friendly Market on the city’s East Side reflects social understandings of Black geographies in Buffalo, he deliberately chose to terrorize a space with a higher concentration of Black residents.

Interstates help define Black geographies as well as social understandings of who resides and belongs – or does not belong where in urban spaces. This understanding informed the gunman’s location decisions and is consistent with historical white domestic terrorist targeting Black communities for violence in urban spaces throughout the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

In East St. Louis in 1917, in Chicago in 1919, in Little Rock in 1927 and 1957, and in Charleston in 2015. These areas were targeted for violence because they are known to be the spaces where Black residents live. These areas are known to be places where Black people live because of urban policies that formed and informed Black geographies in American cities, and social conceptions of ourselves.

Public cognizance of urban Black geographies has historically been weaponized in violent efforts to enforce white supremacy in America.